We love our butches. In a world where women are expected to be the epitome of femininity, and lesbians are viewed as ‘manly’, butch lesbians overthrow gendered expectations. They persistently assert their right to exist.

Knowing our history means accepting who we are today. It means embracing what makes us different from ‘the norm’ without having those differences warped as a reason why we’re inherently ‘other’ and, therefore, should conform to heteronormative ways of thinking.

Butches are under a lot of pressure to deny their femaleness and admit they’re ‘actually men’ so let’s take a look at some butch lesbians from history who resisted such conversion tactics.

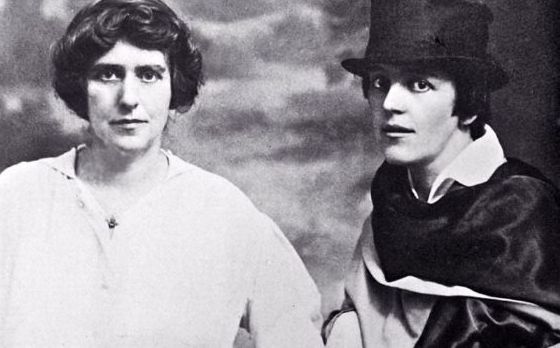

Hannah “Gluck” Gluckstein (1898-1978)

Gluck was a lesbian artist who overthrew feminine expectations. She also rejected categorising her art under any particular movement or genre, preferring to create without conforming to trends. Hannah Gluckstein dropped both her first and surname, preferring ‘Gluck’ instead, which exhibited her rejection of traditional takes on being female. Of course some people today have interpreted Gluck’s neutrality as “genderqueer,” but that’s typical of a society that can’t comprehend diversity and rebellion among females without turning it into proof they rejected their sex.

Gluck cut her hair short and wore sharp suits, which “troubled her father in particular,” writes Hettie Judah for the New York Times. Born into a “wealthy and close-knit London Jewish Family,” Gluck’s father continued to support her financially — despite the disapproval of her nonconformity — “that allowed her to live an elegant and artistic life.” She had a “custom-built studio and frequented the theater and cabaret, a passion that provided a theme for ‘Stage and Country,’” her second exhibition, held at the Fine Art Society of London.

Gluck had passionate romance in her lifetime. She spent holidays in North Africa with florist Constance Spry, which brought with it a “mania for plant and flower portraits.” Gluck immortalized her love affair with Nesta Obermer in the double portrait “Medallion,” as a “true twinning of souls, though it was to cause her both joy and heartache.” The painting later became the cover of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness.

Marguerite Antonia “Radclyffe” Hall (1880-1943)

Radclyffe Hall was a butch lesbian and lesbian drama sure did follow her. At 27, Radclyffe met Mabel Batten, 51, a well-known singer who was married with a daughter and grandchildren, and the pair fell in love. When Mabel’s husband died, they even lived together. Then, in 1915, Radclyffe Hall fell in love with Mabel Batten’s cousin, Una Troubridge, a sculptor married to Vice-Admiral Ernest Troubridge. Una and Radclyffe were a couple until Radclyffe’s death, almost 30 years of which Radclyffe Hall was hardly faithful.

Radclyffe Hall wrote the haunting, lesbian masterpiece The Well of Loneliness (1929), to which there has been much controversy — in and outside of the lesbian community. It was banned by heterosexual society, but The Well of Loneliness is also hated by some contemporary lesbians for being “out of step with the discourse of gay pride.” During the 1970s, when the bizarre idea that any woman could ‘choose’ lesbianism as a feminist act came to fruition, the novel was attacked for “equating lesbianism with masculine identification…its mannish [sic] heroine, its derogation of femininity, and its glorification of normative heterosexuality were anathema.” Butch lesbians are not less female for their lack of conformity to feminine expectations and it is anti-feminist to suggest so.

Mabel Hampton (1902-1989)

Mabel Hampton was an iconic lesbian activist, member of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and dancer. She met Lillian Foster in 1932 and they remained together until Lillian’s death in 1978. Meeting Lillian changed Mabel Hampton’s life. “While waiting for a bus, she meets a woman even smaller than herself, ‘dressed like a duchess’,” according to Joan Nestle.

Mabel ran away from her abusive aunt and uncle, who she lived with after her mother was poisoned when Mabel was a child, and she ended up a dancer during the Harlem Renaissance. That’s when she discovered she was a lesbian, but it was still a few years before she found the love of her life: Lillian Foster.

Romaine Brooks (1874-1970)

Romaine Brooks, born Beatrice Romaine Goddard, was one of many “out” lesbians in the first half of the twentieth century. Romaine is known for her many portraits of women, especially during the 1920s. The portraits reflected her point of view about gender expectations; she challenged the “conventional ideas of how women should look and behave,” in both her art and life, according to American Art.

Romaine “adopted a muted palette primarily of black, white and various subtle shades of gray, sometimes with highlights of ochre, umber, or red.” She portrayed women in a more serious, fleshed-out way than traditional, overly-feminine artistic depictions done by men.

In 1924, Romaine Brooks and Gluck agreed to paint one another’s portraits. Romaine entitled her portrait of Gluck Peter, A Young English Girl — ‘Peter’ was a name Gluck used among friends — and it appears the sitting went well because the portrait was finished. However, Gluck never finished Romaine Brooks’ portrait because the friends had a tiff during the sitting.

Romaine Brooks was in love with heart-throb Natalie Barney for most of her life:

“It was a Friday evening in 1914 and the American novelist and playwright Natalie Clifford Barney was throwing a garden party in Paris,” according to The Paris Review. “Barney’s salons were particularly known as gathering places for lesbian and bisexual women. That night, the painter Romaine Brooks had, true to character, shown up alone.”

“An American born in Rome, Brooks was already becoming known for her uniquely dark and somber portraits of women. That Friday—and over the course of many Friday salons—in the cool of Barney’s garden, she and Brooks fell in love and would remain so for the rest of their lives. However, their disagreements, which became famous in their circle, often exploded in their art—to great creative success. Brooks was a loner—she disliked parties and much of the social jockeying on which Barney thrived. Barney, on the other hand, adored social energy and refused to have a monogamous relationship. She dated a string of other women, including Élisabeth de Gramont (a descendant of Henry IV of France) as well as the socialites Janine Lahovary and Dolly Wilde (niece of Oscar), which put pressure on her relationship with Brooks.”

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946)

Gertrude Stein wasn’t backwards in naming her contribution to literature. She wasn’t the meek and mild, self-deprecating woman the turn of the 20th century expected her to be. “Twentieth-century literature is Gertrude Stein,” she said and, when an audience member asked her why she didn’t write the way she spoke, Gertrude responded, “Why don’t you read the way I write?” It’s easy to see how this attitude would be required in order to live life as bravely, and self-assured, as she did.

Despite her venomous quips, Gertrude was known as a warm person. “She was large, though not in height. In portraits and photographs her eyes look thoughtful, her face strong…Her handshake was warm, her laugh infectious and her hair brown. She liked loose comfortable clothes with deep pockets and she wore sandals over her socks in winter…people valued her friendship and opinion and had a good time in her company,” Diana Souhami writes.

Gertrude and Alice B. Toklas were together for four decades, until Gertrude’s death. They held a ‘salon’ in their home in Paris and invited expatriate American writers like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, as well as artists including Picasso and Matisse.

Gertrude wrote Alice many passionate love letters, as well as cute, mundane domestic notes. Some have been kept and scanned, including the one below.

“My Dearest,

Because I didn’t say goodnight – and I miss it so – please know how much I love you. Gertrude dearest. Good night.”