Leading up to the Second World War, many women — including lesbians — abandoned expectations enforced upon them and moved to like-minded communities, like Paris. Here they wrote, published, and lived lives of their own choosing, far away from their repressive origins. Diana Souhami focuses on the lives of Sylvia Beach, Bryher, Natalie Barney and Gertrude Stein in her upcoming book, No Modernism Without Lesbians, which will be released on May 1. In the book, she argues that lesbians were “the vanguard of modernism, the shift into twentieth-century ways of seeing and saying.”

The lives and contributions of these four lesbians, who played a significant role in art and literature, illuminates the way lesbian work is often undervalued or discredited in comparison to those who aren’t lesbian. While many people uphold James Joyce’s Ulysses as a “masterpiece,” I wonder if they know that it was lesbian Sylvia Beach who published it at her bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, when nobody else would? A book considered “life-changing” by many might never have been published at all if it wasn’t for one pioneering lesbian, and the others who supported her.

Through examining these four lesbian lives, we’re catapulted into the lives of so many more lesbians who could have their own chapters; including their lovers, life partners, friends, and substitute family. This network of modernist lesbians was far-reaching. It is something to behold, treasure, and be proud of.

Paris

Paris is a character in the story of modernist lesbians. “England was consciously refusing the twentieth century,” Gertrude Stein is quoted as saying in No Modernism Without Lesbians, “Paris was where the twentieth century was.” Souhami locates Paris as the flame for lesbians all over the globe, “lesbians with voices to be heard, who would not collude with silence and lying about their existence, got out if they could in order to speak out.” In Paris, lesbians “formed their own community, fled the repressions and expectations of their fathers, took same-sex lovers, and painted, wrote and published what they wanted.”

While Paris worked for the lesbians in No Modernism Without Lesbians, Paris’ experimental, boundary-pushing vibe led to an “anything goes” mentality, which justified predatory behavior in those we revere. Much to my dismay, bisexual French feminist Simone De Beauvoir even supported those who did. French lesbians of today are standing up against the deceptively “progressive” art and intellectual culture in Paris. French lesbian actor Adele Haenel walked out of France’s national cinema awards in February 2020, when Roman Polanski won “best director.” This has nothing to do with censorship or supporting “cancel culture.” Pedophilia and rape cross the line. “Artistic experimentation” has justified the unjustifiable. Polanski should be locked up, not just “cancelled.” Like Haenel said, “Distinguishing Polanski is spitting in the face of all victims. It means raping women isn’t that bad.”

Despite its downfalls, France offered an environment for lesbian art, fashion, and community, embodied by Le Monocle, the Parisian nightclub made especially for lesbians.

Sylvia Beach

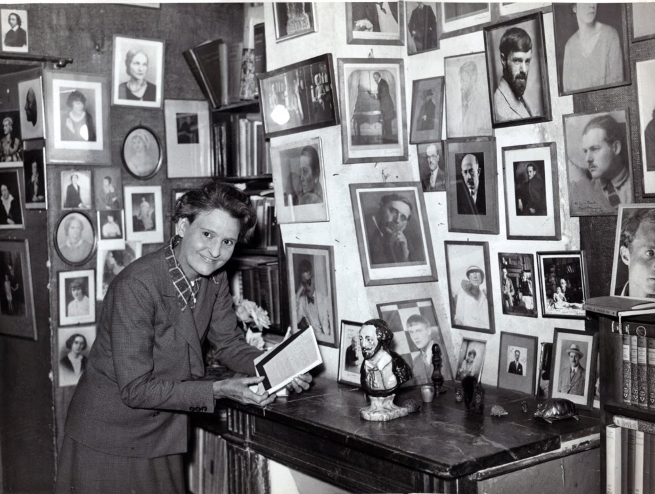

Diana Souhami quotes that Sylvia Beach’s loves “were Adrienne Monnier, James Joyce and Shakespeare and Company”: her life-long partner Adrienne, the author of the novel she published when the “custodians of morality (all men)” censored it as obscene, and the bookshop she founded in 1919 which still honours her today. Like what seems to be the story of many lesbians, Sylvia was born into a very religious family — Presbyterian ministers — but gave up the church and found faith in books. Sylvia said that “books were the friends of her childhood.”

It is no wonder why Sylvia moved from America to Paris, the centre for art and ideas. “Books opened doors to freedom, shaped her thinking and feelings and gave her courage to rebel,” Diana Souhami states, but mentions that Sylvia also took with her an “inherited morality,” that she’d need in experimental, fluid Paris. The principles Sylvia maintained as part of her value system were “no indulgence, concern more for others than herself, work as contribution rather than personal profit.” She thoughtfully adopted parts of what she learnt over time to her personality, but only what made sense to her, abandoning that of which was intended to hate, corrupt or control.

Sylvia was not a great business woman because she didn’t prioritise money. She had to “appeal to relatives and wealthy friends for money” — she owned Shakespeare and Company simply for the love of books — she was “too generous and idealistic ever to earn much.” However, when it came to standing up for what was right, she wasn’t at all hesitant. Diana Souhami writes, “when racism and sexism reached a zenith of viciousness with Hitler and his Third Reich, [Sylvia] remained in Paris as the German army marched in. She was interned in a concentration camp for having employed and protected a Jewish assistant, for being American and for stocking Jame Joyce’s Finnegans Wake in her bookshop, but not for being lesbian.”

Sylvia kept her sexuality private and perhaps that’s what saved her from being killed. Diana Souhami states that “she was always a lesbian, a feminist and a suffragist, even though she chose not to talk about her sexuality.” It brings up a good point: sexual orientation exists outside of our comfortability with it. Even when historical lesbians were — often understandably — tentative about using direct language to describe their sexual orientation, if they speak of only experiencing same-sex attraction and/or are not connected to any men and spend their entire lives chasing women, then it’s safe to say they’re a lesbian. Lesbianism isn’t something we have the power to change the meaning of, to personally identify in and out of at a whim, it describes a reality that exists outside of language. Even women who are uncomfortable with using the term “lesbian” for whatever reason are still lesbian if they only experience same-sex attraction.

Bryher

Bryher was a patron of modernism. She’s quoted as saying “I have rushed to the penniless young, not with bowls of soup but with typewriters.” Bryher was born into a multitude of money and used it to support rebellious writers who otherwise would have been systematically denied the money and time to write. She was the “rock and saviour of her partner, the poet H.D. – Hilda Doolittle,” she “funded the Contact Publishing Company in Paris,” she “supported James Joyce and his family with a monthly allowance,” she “gave money to Sylvia Beach,” and “subsidized Margaret Anderson’s Little Review in New York.” She also financed experimental films and founded Close Up, “the first film magazine in English.”

Born Annie Winifred Glover, she used the name ‘Bryher’ to distance herself from the ultra-femininity expected of her. Like Radclyffe Hall — born Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall — who also went by “John” after a lover discovered Hall’s resemblance to one of her ancestors of the same name, and lesbian painter, Hannah “Gluck” Gluckstein, Bryher had barbered hair and changed her name, which Diana Souhami states “declared resistance.” Bryher is quoted as saying “I was completely a child of my age,” which Diana Souhami outlines was a reference to modernism: “Bryher’s allegiance was to new ways of saying and seeing, civil liberties, [and] gender equality.”

Bryher put herself on the line without the same self-consciousness seen in other lesbians of the time. She entered two “lavender marriages” with gay men, one “to secure her inheritance and pacify her parents, the other to secure adoption rights for H.D.’s child.” Even though she had a bauhaus inspired house in Switzerland and had quite radical politics, Bryher liked “unfussy food (toast and Yorkshire pudding), seemed humourless, stayed quiet when others were talking and was overlooked in a group.” While people were glad to receive her help, Souhami reports that “no one fell in love with her.” In saying that, Bryher and Sylvia Beach were close friends for almost half a century, “They confided, corresponded and looked out for each other even when living in different countries.”

Natalie Barney

Natalie Barney had no intention of hiding her lesbianism. She said “I am a lesbian. One need not hide it nor boast of it, though being other than normal is a perilous advantage.” She “went where desire led her.” For Natalie Barney, modernism’s rejection of strict rules on narrative and form extended to her private life. She had many lovers, sometimes more than one at once, claiming “love has always been the main business of my life.” She met her last lover on a sea-side bench in Nice when she was eighty.

Natalie was rich. Diana Souhami indicates that, perhaps, her wealth led her to feelings of entitlement. In some ways love was a game to her, saying “One is unfaithful to those one loves so that their charm will not become mere habit.” While Natalie had a lot of women in love with her, monogamy wasn’t her goal. Orgasms were. She wrote that when she was a child, at bath-time, “the water that I made shoot between my legs from the beak of a swan gave me the most intense sensation.” This sexual epiphany led to a rich sex life when she became an adult.

Natalie’s violent, alcoholic father inspired her rebellious nature. Diana Souhami states that “defying him was an essential component of Natalie’s freedom.” Natalie wrote, “I neither like nor dislike men, I resent them for having done so much evil to women. They are our political adversaries.” She became a feminist while travelling Europe in her teenage years with her mother. She saw the way women were treated so badly and rejected the belief that a woman’s only purpose was to be a wife and mother. “The finest life is spent creating oneself, not procreating,” she said.

Natalie was very open about her lesbianism. Diana Souhami states that her “inspired contribution was to be transparent about same-sex desire in a repressed and repressive age…she led by candid example.” She stirred the same assuredness in other lesbians, motivating them to express their sexual orientation without regret, saying “why should I bother to explain myself to you who do not understand – or to you who do?”

Gertrude Stein

Despite being in a loving, committed life-partnership with Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein wasn’t always keen to discuss it publicly. Gertrude wasn’t ashamed of her relationship with Alice, there are multitudes of photographs and art made about the pair, but she was quick to guard their privacy. Virgil Thomson said, “the two things you never asked Gertrude, ever, were about her being a lesbian and what her writing meant.” Perhaps this is because both were clearly linked, she wrote many love letters to Alice B. Toklas. Talking about her writing meant talking about their relationship.

“I like all the people who produce and Alice does too and what they do in bed is their own business and what we do is not theirs.”

– Gertrude Stein

Gertrude wasn’t backwards in naming her contribution to literature. She wasn’t the meek and mild, self-deprecating woman the turn of the 20th century expected her to be. “Twentieth century literature is Gertrude Stein,” she said and, when an audience member asked her why she didn’t write the way she spoke, Gertrude responded, “Why don’t you read the way I write?” It’s easy to see how this attitude would be required in order to live life as bravely, and self-assured, as she did.

Despite her at times venomous quips, Gertrude was known as a warm person. “She was large, though not in height. In portraits and photographs her eyes look thoughtful, her face strong…Her handshake was warm, her laugh infectious and her hair brown. She liked loose comfortable clothes with deep pockets and she wore sandals over her socks in winter…people valued her friendship and opinion and had a good time in her company,” Diana Souhami writes. Gertrude was clearly a woman of comfort. Whether it be eliminating the questions she wasn’t comfortable answering, or wearing clothes that made her cozy, Gertrude valued what felt right to her and Alice.

“Think of the Bible and Homer think of Shakespeare and think of me.”

Gertrude Stein

Paris many Black u.s. jazz artists like miles davis liked there. And James Baldwin. Theres an article on out dot com of 7 Paris lgbt ppl cotemporay now but I ain’t read it. French rap is allegedly the best rap after u.s. rap. And important ideas like albert camus n sartre n I fink franz fanon but I ain’t sure. I heard dat Germany had da first lgbt movement but hitler soon crushed that like he destroyed everything. The until 70s there wasn’t rally lgbt movement on lanet rally. So they say iono fo sho